Forsaking Food Security

by Chris Dick and Beth Jarosz

How often are Americans concerned that their food will run out before they have money to buy more? Or that they did not have the money to eat balanced meals? How many families with children had to skip meals because there was not enough money for food?

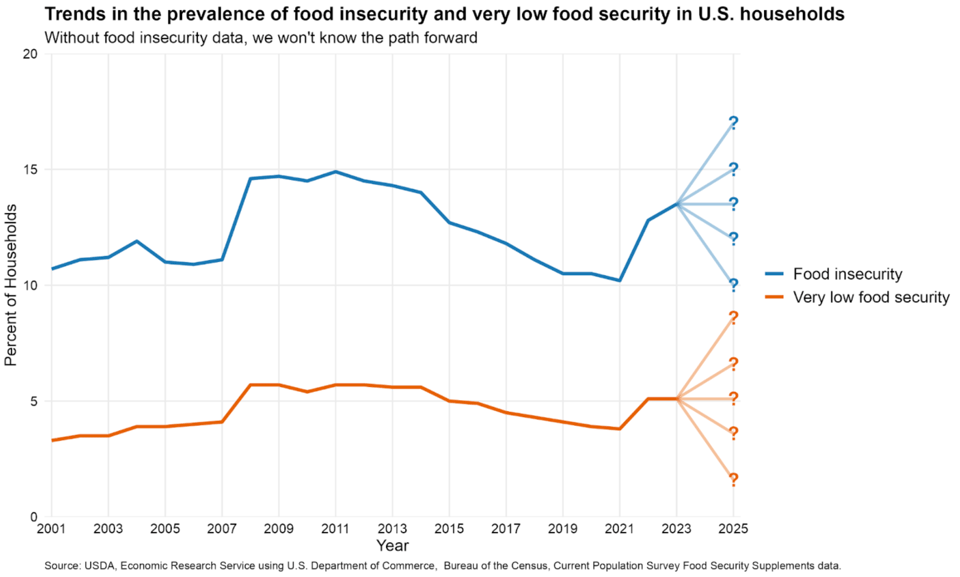

For decades, we have been able to answer these questions and more because of the Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement (CPS-FSS) as well as a yearly report put out by the USDA’s Economic Research Service. But, we are about to know a whole lot less.

According to the Wall Street Journal, USDA is pulling funding from both the CPS-FSS as well as the resulting report beginning with the data from 2025 that would be released in the fall of 2026. We still think that the language of both the press release as well as the statements from USDA lack some clarity on this point–the terms “survey” and “report” are used interchangeably–and are trying to confirm if it is the report that is being cancelled, or the report AND the data collection. Either way, we’ll be losing critical data.

The reason? According to the USDA press release: “These redundant, costly, politicized, and extraneous studies do nothing more than fear monger.”

Are those reasonable explanations for terminating the survey and report?

Let’s take each argument in turn.

Is this a redundant or extraneous study?

It is difficult to believe the food security survey is redundant or extraneous. CPS-FSS is the most comprehensive source of information on food insecurity in the U.S. While other data collections provide glimpses into food insecurity (such as data from the American Community Survey on Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation, the National Survey of Children’s Health on whether or not households with children could afford nutritious meals, or school district data on participation in free and reduced price meals programs), there simply is no other source that provides comparably robust data on hunger and ability to afford food.

Is it costly?

In 2024, the total cost of CPS-FSS data collection and methodology research was less than $1.1 million dollars ($1,058,692, to be exact), and in some recent years the cost has been substantially lower (just $710,000 in 2022). While one million dollars might sound like a lot of money on its own, it is a tiny fraction of the federal budget. To put the cost into perspective, a single, one-way, cross-country flight on Air Force One is estimated to cost about $1 million ($177,843 per hour). That small amount of funding for data collection informs more than $100 billion dollars in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program funding, a level approximately 100,000 times greater than the cost of the data. In addition, the CPS-FSS data informs state and local hunger-abatement programs nationwide.

Is the study politicized or “fear mongering?”

Very simply: no. Reporting that food insecurity has gone up, down, or stayed the same is not partisan. Hiding data if it does not advance a particular agenda is.

The federal statistical system is structured to be objective and independent. While outside groups of any political ideology may use the resulting data to emphasize points that advance their goals, the data collection and reporting itself is designed to minimize bias and political influence. Whether a party’s policies are (or aren’t) working, the public should have access to the evidence.

What are we actually losing?

The CPS-FSS asks the following 18 questions (the first 10 are for all households and questions 11-18 are only for households with children).

1. “We worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more.” Was that often, sometimes, or never true for you in the last 12 months?

2. “The food that we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more.” Was that often, sometimes, or never true for you in the last 12 months?

3. “We couldn’t afford to eat balanced meals.” Was that often, sometimes, or never true for you in the last 12 months?

4. In the last 12 months, did you or other adults in the household ever cut the size of your meals or skip meals because there wasn’t enough money for food? (Yes/No)

5. (If yes to question 4) How often did this happen—almost every month, some months but not every month, or in only 1 or 2 months?

6. In the last 12 months, did you ever eat less than you felt you should because there wasn’t enough money for food? (Yes/No)

7. In the last 12 months, were you ever hungry, but didn’t eat, because there wasn’t enough money for food? (Yes/No)

8. In the last 12 months, did you lose weight because there wasn’t enough money for food? (Yes/No)

9. In the last 12 months, did you or other adults in your household ever not eat for a whole day because there wasn’t enough money for food? (Yes/No)

10. (If yes to question 9) How often did this happen—almost every month, some months but not every month, or in only 1 or 2 months? (Questions 11‒18 were only asked if the household included children ages 0‒17)

11. “We relied on only a few kinds of low-cost food to feed our children because we were running out of money to buy food.” Was that often, sometimes, or never true for you in the last 12 months?

12. “We couldn’t feed our children a balanced meal, because we couldn’t afford that.” Was that often, sometimes, or never true for you in the last 12 months?

13. “The children were not eating enough because there wasn’t enough money for food.” Was that often, sometimes, or never true for you in the last 12 months?

14. In the last 12 months, did you ever cut the size of any of the children’s meals because there wasn’t enough money for food? (Yes/No)

15. In the last 12 months, were the children ever hungry because there wasn’t enough money for food? (Yes/No)

16. In the last 12 months, did any of the children ever skip a meal because there wasn’t enough money for food? (Yes/No)

17. (If yes to question 16) How often did this happen—almost every month, some months but not every month, or in only 1 or 2 months?

18. In the last 12 months, did any of the children ever not eat for a whole day because there wasn’t enough money for food? (Yes/No)

As additional reasoning for cancelling the study and survey, the USDA press release goes on to state that increases in SNAP funding from 2019-2023 did not lead to decreases in food insecurity. But the point of any data collection is not to report only on successes. In fact, data can be the most valuable when they show that policy solutions haven’t been working.

In 2019, President Trump signed the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act into law. That law states that statistical agencies must “identify ways in which agencies can improve upon the production of evidence for use in policymaking.” Cancelling CPS-FSS collection flies in the face of that goal.