Are We Ready for 2025 Wildland Fire Season?

Modeling the Impact of Recent Workforce Policy on Federal Program Delivery

by Bernie Kluger

Among the datasets prominent in America’s Data Index is the quarterly tally of federal personnel, known widely as FedScope. The US Office of Personnel recently confirmed that it would resume an investment initiated under previous agency leadership to accelerate the release of this data to the public. Although this assurance is welcomed, it is insufficient given the rapid succession of disruptions to federal personnel.

Data on federal employment must also include information on what work those employees are doing. Unfortunately, the publicly available FedScope data does not routinely provide detail showing how federal agencies have deployed personnel to field sites, programs, or functions. Given the continuing lack of transparency, data scientists have an expanding role in determining, with the limited amount of data publicly available, which programs are at greatest risk of failure due to ongoing personnel disruption.

On June 21, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced that the USDA Forest Service had “hired 96% of its 11,300-firefighter hiring target with full staffing anticipated by mid-July.” The annual hiring surge is a long-standing practice at the USDA Forest Service and a foundational component of the national wildland fire strategy. So, at first glance one would assume that USDA was on track with its preparations for the 2025 wildland fire season.

However, expecting a sigh of relief from residents in fireshed communities, the Agriculture Secretary instead found herself deflecting concerns that despite progress in hiring front-line firefighters, widespread workforce reductions in supporting roles across the USDA Forest Service would undermine the effectiveness of the overall wildland fire mission, placing “lives, property, and our environment at greater risk.” Determining which is true will have a profound impact on USDA’s firefighting partners – and the communities in the path of this year’s fires.

Similar discussions about the potential impact of federal workforce reductions is now underway wherever the federal government provides essential services, ranging from air traffic control to nuclear stockpile management. Do recent federal personnel policies reflect a shrewd focus on efficiency and mission critical jobs or have personal cuts been so broad as to fundamentally undermine federal delivery capacity? The answer will shape how business leaders, state, local, and tribal government, and non-profit organizations deploy their own resources in the coming months to mitigate potential gaps in federal services in order to prevent harm.

This article recommends a strategy for answering these important questions, not only for wildland fire management, but across all of the essential functions of the federal government where agencies have eliminated jobs performing both front line services, like firefighting, and also support functions, like scientific research, field data collection, acquisition management, and human resources.

The Situation: Widespread Personnel Reductions

As of the writing of this article, federal agency leaders have pursued four rounds of downsizing. In February 2025, USDA and other federal agencies announced the termination of all probationary employees. In response to litigation challenging the legality of these terminations, as well as the realization among agency leaders that they had removed employees in essential positions like nuclear security and food inspection, agencies announced that employees could return to their jobs. However, it is unclear how many new employees remain to support the wildland fire mission this summer; reporting suggests workers have rejected reemployment offers or returned only to find themselves placed in administrative limbo. Among more experienced employees, federal leadership followed up with two rounds of voluntary separation agreements across the federal government. The media has also reported on what amounts to a de facto campaign to pressure the federal employees in senior leadership positions to resign or retire. Trends in retirement data suggest the campaign is working, with retirement rates at more than double historic levels in May 2025.

The Problem: Information Asymmetry Between Federal Agencies and the Public

Amid the swirl of news, official statements, and litigation, the question remains among policy-makers and business leaders how federal workforce reductions will impact specific policy areas. Although the US Office of Personnel Management has released some agency-level data and, in fact, has done so ahead of schedule, barriers remain to informed interpretation of that data. An embargo on communication between agencies and the public and the administration’s dismantling of the federal workforce data team have eliminated trusted lines of communication through which the public could obtain information on how workers are actually deployed. Lacking insights into the available data, journalists and advocates have resorted to hyperbolic, flattening terms like “gutted” or “hollowed out” that obscure the size, nature, or location of impact, and perhaps engender a sense of hopelessness. Speculation is rampant, with articles citing anecdotal evidence ranging, for example, from high profile airline disasters to the social security payment errors as proof of the harm caused by cuts at the Department of Transportation or the Social Security Administration. Greater precision is needed in our understanding of who has been terminated, what work they were performing, and how their work impacts the public.

The Challenge: Building a Model with the Data We Have

What is needed is a fact-based method for determining which specific federal functions are at greatest risk of failure. The next section of this article outlines one promising approach, using the example of wildland firefighting at the USDA Forest Service. My hope is that the data science and academic research community will be inspired by this roadmap to model with greater precision the specific impact of federal workforce cuts to wildland firefighting, and to pinpoint which geographic locations or support functions are at greatest risk of failure. I would also encourage anyone who pursues this line of analysis to extend the model to other federal functions and to share their findings widely with policy makers, business leaders, and the general public.

Case Study: Wildland Fire and the USDA Forest Service

As one of three federal agencies responsible for wildland fire management, USDA Forest Service leadership monitors hiring targets as intensely as weather models and forest health assessments to gauge what kind of fire season is ahead. Although USDA may be on track to meet its summer firefighter target, USDA leadership has removed from active duty employees in supporting roles ranging from forest health management to information technology.

Given the potential public harm, it is a matter of public safety and national security to identify how recent policies may specifically prevent the USDA Forest Service from meeting its responsibilities. Wildland fire managers expect 2025 to be tougher than normal throughout the Pacific Northwest and central Texas. In this context, a personnel shortfall could result in greater loss of life, as well as habitat and property, in those regions. This raises the question whether federal, state, local, and tribal fire officials in those regions must prepare now for the possibility of gaps in USDA Forest Service capacity that could threaten the lives of USDA’s 11,300 firefighters, local fire crews, and the people who live in the path of this year’s wildfires.

I would argue that despite the lack of transparency, the available data does provide some indication of where personnel actions at the USDA Forest Service and other federal agencies may push systems to the breaking point. Working in favor of the analyst is the overall stability of federal personnel trends over the 20 year period for which we have public data (Figures 2, 3, 4). Even in extremely lean hiring years, such as during the 2013 government shutdown (Figure 3), USDA Forest Service workforce trends, as with most federal agencies, return quickly to the mean.

Workforce Projection Roadmap

A review of long-term employment trends, the most recently available public data, and sparse USDA reports to Congress suggest that as a whole the USDA Forest Service may be short by as many as 10,000 employees this summer, with direct consequences on the federal government’s capacity to meet its responsibilities. The following provides a roadmap showing how, with limited analytics, I arrived at this estimate, and how someone with deeper skill might disaggregate this number to identify the states and functions at greatest risk.

1. Annual Attrition and a de facto Hiring Freeze: Up to 3400 Employees Removed

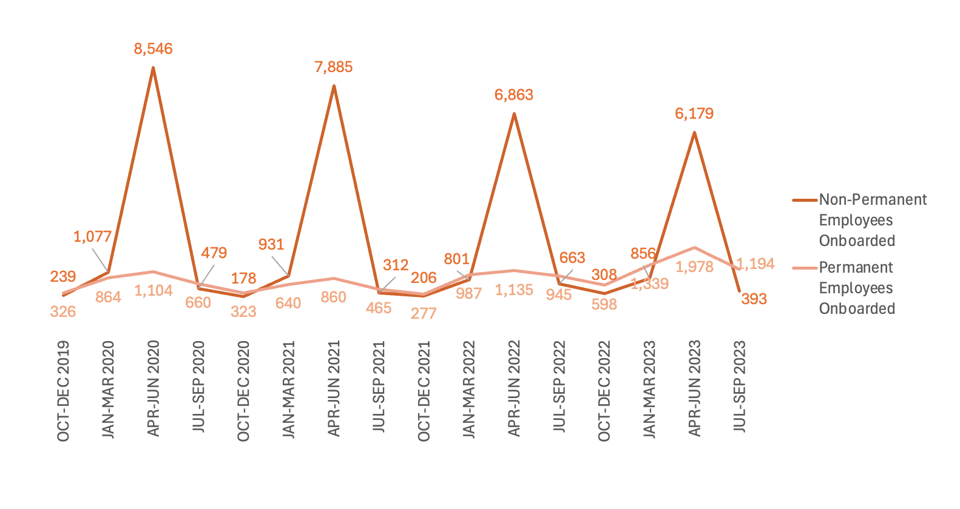

The USDA Forest Service on average adds 3400 permanent workers each year to replace retirees and other separating employees. This routine annual process peaks (Figure 1) in the first half of the calendar year, which in 2025 is also when USDA leadership abruptly introduced a broad hiring freeze and enlisted human resources staff in planning for and implementation of workforce reductions.

2. Probationary Employee Dismissal: 2000 to 4700 Employees Removed

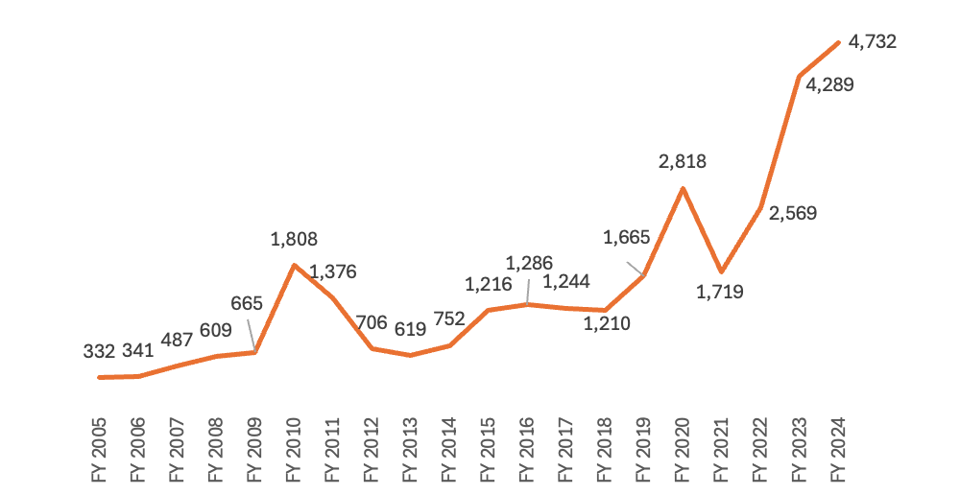

The exact number of probationary employees is not available, but one could approximate the number of potential separations from recent hiring data. As a rule of thumb, federal probationary employees are those who have served for less than one year in their current position. Unfortunately, neither the US Office of Personnel Management nor USDA have published updates on hiring activity after September 2024. What is known is that on September 30, 2024, six months before USDA began the separation of probationary employees, federal data show 4732 USDA Forest Service permanent employees with less than one year of experience (Figure 3). Many of those employees are likely to have separated in the normal course of employment or reached their one year anniversary before USDA implemented the policy, a set of facts that establish 4732 as a maximum or “ceiling” for the number actually removed. As a floor, we can look to the recent minimum hiring level in a typical year; in FY 2024 the USDA Forest Service hired only 1940 permanent employees who were new to federal service and vulnerable to involuntary termination as probationary employees.

3. Voluntary Separation: 3100 Employees Removed

USDA implemented two rounds of the voluntary separation program known as “the Fork” or Deferred Resignation Program (DRP), which are reported to have resulted in 3100 separations.

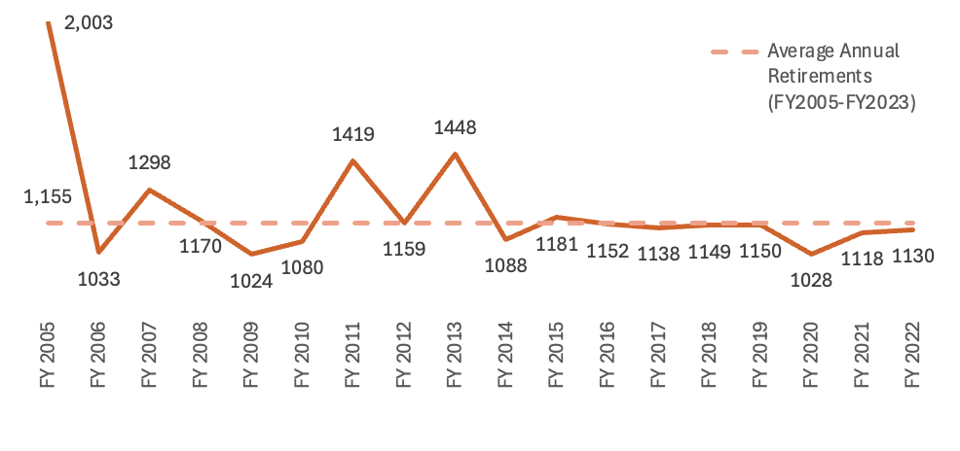

4. Other Early Retirements: Up to 1100 Employees Removed

Official reports of government wide retirement filings show that federal employees retired in May 2025, a typically low month, at the same level as the typical peak month of January. The typical number of USDA forest Service employees filing for retirement annually is 1100 (Figure 1). If one assumes USDA Forest Service employees followed this trend, one might expect that up to 2200 USDA Forest Service employees may have filed for retirement in January 2025 and May 2025 combined. A doubling in the normal level of retirement would represent over 25% of all USDA Forest Service employees with 20 or more years of experience. (Estimate is presented as “up to 1100” since it is unclear how many participants in the two rounds of voluntary separation filed for retirement in May 2025 or whether the peak in May 2025 is an acceleration of retirements that would have come later in the calendar year.)

Identifying Where Personnel Reductions Are Creating the Greatest Risk

The next step would be to determine how the removal of 10,000 USDA Forest Service employees would immediately undermine wildland fire management. In my personal experience, the USDA Forest Service operates as a highly integrated whole in which every employee has a role in wildland fire management, whether smokejumpers fighting fires in the field, contract officers planning logistics at the scale of a military campaign, or headquarters attorneys volunteering for temporary assignment in the fire camps. However, it should be possible to identify areas of acute risk.

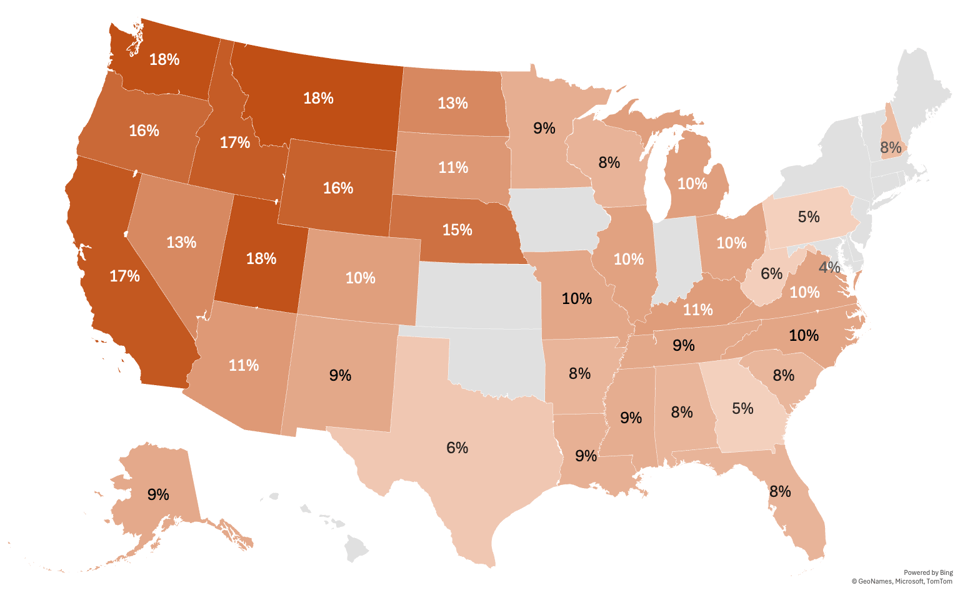

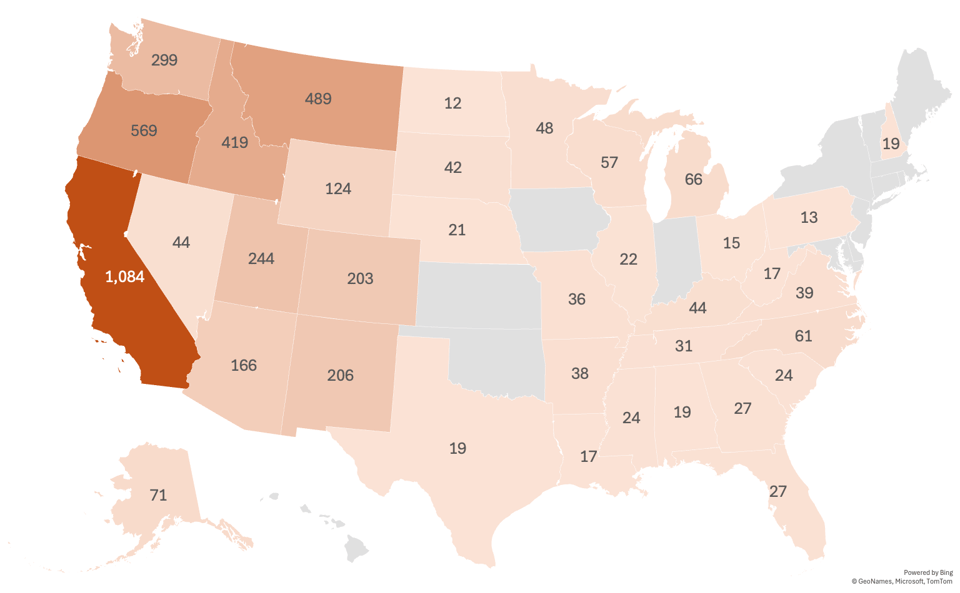

Much of work of wildland fire management is concentrated in field offices in California, Idaho, Montana, or Oregon that have a direct or supporting role in wildland fire management and hire large numbers of permanent employees every year (Figure 5). Relevant offices could be identified in collaboration with experts in the non-profit community, employee associations, and among state, local, and tribal fire management authorities. Some of these offices are quite small or have very high turnover and therefore vulnerable to the particular broad-brush workforce reduction strategies that USDA has implemented. Analysis based on the above should provide a picture of the current state of the available USDA wildland fire workforce, or at least “floor” and “ceiling” estimates for the current level of staffing across different work locations and functions. This would then provide a mapping of which functions are at greatest and least risk.

Moving from Problem Identification to Evidence-Based Solutions

With an evidence based projection of current local staffing levels in hand, the research community can determine the extent to which recent workforce policies – termination of probationary employees, voluntary separation programs, and pressure on experienced employees to retire – are also reducing wildland fire management capacity. It is worth noting that Washington State, which does not have one of the largest pools of workers, is one of three states with first year employees constituting 18% of its workforce, making the state firefighting workforce especially vulnerable to termination of new employees (Figure 6). In a policy area like wildland fire, state and local policy makers, public advocates, and business leaders in Washington State, and in other vulnerable locations, would then have a reasonable projection of this summer’s overall capability shortfall. State, local, and tribal fire teams may then use this analysis to begin preparations for mitigating gaps in the federal workforce, such as expanding local fire teams or expanding interstate resource sharing agreements.

Next Steps

Assembling a Government Wide Federal Personnel Model

Foundational work is already underway in the non-profit and academic sector to quantify the impact of federal personnel reductions on the public. The Impact Project, Volcker Alliance, and Civic Leadership Education and Research (CLEAR) Initiative have leaned into the work of bringing together the organizations and researchers with expertise and data related to the federal workforce. In the coming months, they will have an important role to play in the establishment of a new research and data analytics collaborative.

Extending the Model to Other Federal Services

With historical trends and available current data, it should be possible to model where a federal agency, such as the USDA Forest Service, is most likely to experience acute capacity gaps that put the public at immediate risk. A first round of analysis might focus on agencies that, like the USDA Forest Service, have similar characteristics that exacerbate the vulnerability of their work to personnel cuts: high turnover among new employees, intense competition for talent with other public and private sector employers, and a high likelihood of immediate harm to the public if their function were interrupted. Agencies meeting those criteria would include those on the front lines of food processing, cybersecurity, nuclear stockpile management, medical care, and disaster relief. Government oversight functions, such as fraud detection, whistleblower protection, and financial controls, might also be included in a first round of analysis.

Supporting Long Term Collaboration Among Stakeholders

Over the long term, a shared source of reliable projections of federal capacity could inform policy makers in state, local, and tribal government as well as industry, non-profit organizations, and philanthropy, about where personnel changes will most likely lead towards success or failure in public service infrastructure. Leveraging proven techniques and existing non-federal data sources, we can pinpoint which federal workforce changes are most likely to impact – positively or negatively – the delivery of federal programs and support policy makers in formulating evidence based policies to preserve the health, safety, and prosperity of all Americans.

Figure 1: USDA Forest Service Quarterly Onboarding of New Non-Permanent and Permanent Employees (FY 2020 - FY 2023)

USDA Forest Service hiring across all professions is highly cyclical, with onboarding of employees peaking in April through June in advance of the peak firefighting and recreation months. Recruitment and hiring, however, is a year-round activity with summer workers submitting applications months in advance. Noticeable in the chart below is also a steady decline in non-permanent employment and increase in permanent employment. In 2021, the USDA Forest Service began offering permanent positions to thousands of seasonal employees in an effort to expand wildland fire prevention in the “off” months.

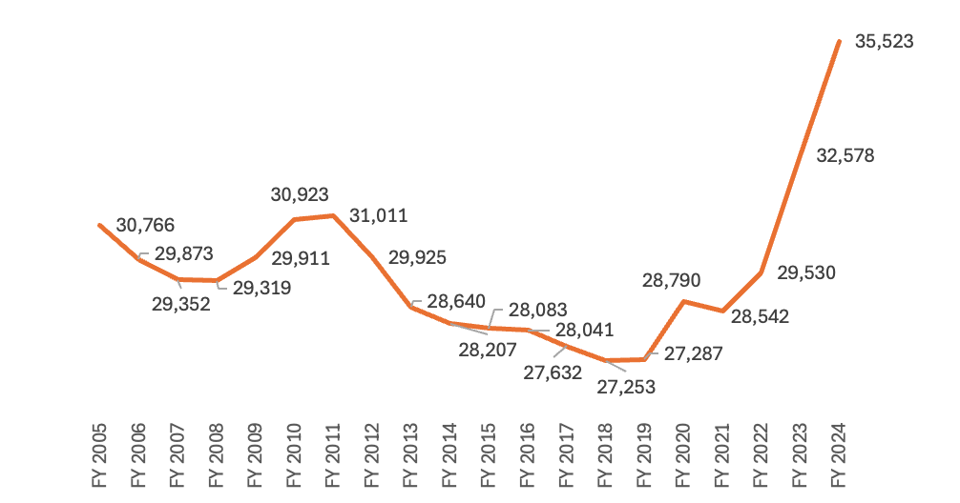

Figure 2: USDA Forest Service Permanent Employees as of September 30 (FY 2005 - FY 2024)

USDA Forest Service permanent year-round employment has been relatively stable for much of the last two decades. Noticeable in Figure 1 and Figure 2 is increase in permanent employment and a steady decline in non-permanent employment. In 2021, the USDA Forest Service began offering permanent positions to thousands of seasonal employees in an effort to invest in wildland fire prevention in the “off” months.This followed several years of downsizing in the overall workforce beginning in FY 2012. Officials expected natural turnover and retirements to restore the USDA Forest Service to previous staffing levels (~30,000) but with a rebalancing towards permanent and younger workforce.

Figure 3: USDA Forest Service Permanent Employees With Less Than One Year of Service as of September 30 (FY 2005 - FY 2024)

USDA Forest Service used one-time funds from annual appropriations, the Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act to recruit a new generation of permanent workers and reduce dependence on seasonal temporary workers. Employees in their “probationary” first year of service have been vulnerable to involuntary termination despite having a role in wildland fire management.

Figure 4: Retirement of USDA Forest Service Employees

Retirement rates at the USDA Forest Service and across the federal government have been remarkably stable since FY 2014. For FY 2025, federal retirement filings are on track to at least double typical retirement rates, suggesting that USDA Forest Service may lose at least 2000 (25%) of employees with 20 or more years of service.

Figure 5: Geographic Distribution of Permanent USDA Forest Service Employees with Less Than One Year of Federal Experience as of 9/30/2024 (N=4725)

USDA Forest Service employment is concentrated in the West, with California home to the largest number of new and total employees. Workers contribute to a wide variety of functions, but wildland fire management is increasingly becoming every employee’s responsibility.

Figure 6: Geographic Distribution of Permanent USDA Forest Service Employees with Less Than One Year of Federal Experience as of 9/30/2024 as a Percent of All USDA Forest Service Employees (N=4725)

USDA Forest Service employment is concentrated in the West, with California home to the largest number of new and total employees. However, as a percentage of all USDA Forest Employees, first year employees constitute 9%-18% of employees in all western states. It is worth noting that Washington State, which does not have one of the largest pool of workers, is one of three states with first year employees constituting 18% of its workforce.

Notes:

Although hiring is at 96% of target, onboarding may be slower than normal. USDA human resources staff, with responsibility for hiring and onboarding of employees, are likely to have been separated from USDA at rates comparable to other work areas. Among the remaining human resources staff, those normally allocated to fire season hiring and onboarding have had their attention diverted to managing terminations and other DOGE initiatives. Based on personal experience, staffing shortages can add weeks or months to onboarding.

FY denotes the federal fiscal year, which begins on October 1.

Other trends worth noting would be the normal separation rate in high turnover jobs in the USDA Forest Service that are presently under a hiring freeze and unemployment claims by federal employees in states that are home to major USDA Forest Service firefighting and logistical hubs.

Bernie Kluger most recently served as a senior advisor at the US Department of Agriculture where he was responsible for department-wide human capital strategy. He is a recognized expert in public sector and non-profit administration, with extensive experience leading change management, organizational development, and turnaround strategy. Follow Bernie at http://www.linkedin.com/in/bskluger/